Exploring soil biodiversity through wonder and taxonomy

The XDF ©NASA

To understand how soil biodiversity and mesofauna fit into a complex, huge and chaotic universe, and why they matter, we first need to look outwards…

Example1.

A few years ago, NASA published a photograph called the XDF, a composite photograph compiled from ten years of Hubble telescope photographs, focusing into one small patch of empty space.

We now know that each smear of light it recorded has had to travel up to 13.2 billion years before reaching the Hubble's camera sensor. And each one of those crazily small patches of light is yet another galaxy, each lit up by its own countless billions of stars.

If you've ever wanted to feel existential angst, or complete, jaw-dropping wonder, now would be the time.

This is, by far, the most awe-inspiring and moving photograph I have ever seen.

A successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, was launched in 2021, to look even further back in time and succeeded, with its remarkable first deep field infrared image of some of the early universe being released on July 12, 2022.

Galaxy cluster SMACS 0723, © ESA, CSA, and STScI

For now at least, the historic Hubble is still functional, and silently drifts, caught in a low orbit, as below, the earth spins us around a small provincial star sitting in part of an insignificant spur of the Milky Way Galaxy.

“Every atom in your body came from a star that exploded. And, the atoms in your left hand probably came from a different star than your right hand.

It really is the most poetic thing I know about physics: You are all stardust. You couldn’t be here if stars hadn’t exploded, because the elements - the carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, iron, all the things that matter for evolution and for life - weren’t created at the beginning of time.

They were created in the nuclear furnaces of stars, and the only way for them to get into your body is if those stars were kind enough to explode.

So, forget Jesus. The stars died so that you could be here today.

― Lawrence M. Krauss”

Example 2.

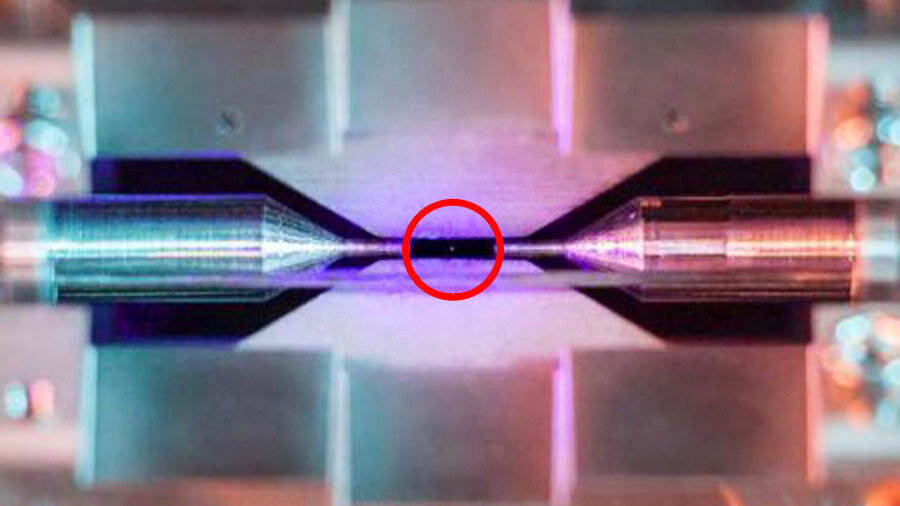

In 2018, David Nadlinger, from the University of Oxford took a photo of a single positively charged strontium atom from some long dispersed supernova, held in a magnetic field. It is a remarkable photo, taken with a Canon 5D mark ii camera, a 50mm lens, some extension tubes, a tripod and a long exposure. It is the first photo of its kind.

Example 3.

This guy below.

Deuterosminthurus bicinctus juv on fruiting fungal bodies, Burrington Combe, February 2019

At one end of my imagined scale, as of 2023, is the furthest observable galaxy, called JADES-GS-z13-0, formed 320 million years after the Big Bang.

Atoms are at the other end of my arbitrary scale.

Between the two, trotting and wiggling about somewhere in the middle of all the other observable stuff in the universe are some tiny invertebrates, like the Deuterosminthurus bicinctus above, a springtail. Together with the other classes of tiny soil animals, they are known as mesofauna.

We have got to a point where a telescope has somehow managed to resolve the light from an infinitesimally small point in space, relatively speaking, in order to see an impossibly far away galaxy.

And a PhD student somehow worked out how to photograph an infinitesimally small, single glowing atom.

Both achievements are amazing testaments to our ingenuity and inquisitiveness as a race.

But if we don’t have a multi-billion dollar Hubble telescope or a multi-million dollar research laboratory to play with, how can we get to explore and experience such hidden, small, amazing things for ourselves?

I think I’m about to finally get to the point.

We have a third and egalitarian option available, luckily, and it’s all thanks to the dirty world of biology. Specifically, soil biology.

The tiny world of soil animals is accessible to us all, with or without a Biology degree. It can be easily discovered and explored by anyone with a cheap hand lens/loupe, curiosity and knees. And through that simple but profound act of kneeling and looking, whether we are in a garden, carpark or a tropical rainforest, we are joining Darwin, Wallace, Beatrix Potter and every other amazing biologist who ever got down on the ground and said, “Good Lord!”, or “Wow!”, depending on your century.

This website is just a glorified version of that, but with a camera.

Wonder and wondering

All forms of science are powered by a sense of wonder. Without it, there would be no passion or drive to discover anything new. Dry, jaded cynicism has never found a new plant or planet. Find someone who studies slime moulds or sub molecular particles and ask them why they do what they do. You'll see them getting as excited as a child in a tree house while they tell you.

I have biologist friends who, between them, study moss, beetles, mites, slime moulds, millipedes, and Collembola, like me. Everyone lights up when conversation is brought around to their pet passion/obsession. It's both endearing and delightful.

Not surprisingly, I love Collembola with all the happy single-mindedness and emotion I can muster. I find them eternally fascinating and beautiful, and I can't think of anything more fun than going around the world, looking at them. When I've done public talks, I've had to be careful how I discuss them as I can choke up. It's emotional stuff.

However, over the years I've had to admit that the other tiny animals I've seen while I'm crawling about in the leaf litter are actually pretty interesting too. So even though it'll always be Collembola that are closest to my heart, this website includes most of the other wonderful tiny stuff that lives in and around soil too.

I'm an amateur, never having studied biology at a university. I've built my clumsy knowledge base through years of researching- reading scientific papers, clocking thousands of hours in the field, taking photographs and specimens and observing the behaviour of thousands of different species around the world. It’s been life-changing.

A mix of mesofauna

Name Calling

You may have noticed across the website that I often use fancy scientific names. It's a tricky one. Some of the world's mesofauna classes have never had common names. Protura can be called coneheads if you're feeling particularly derogatory. Diplura are sometimes referred to as two-pronged bristletails while Collembola quite like being called springtails. Acari are mites. As far as choosing between the larvae of ‘biting midges’ and Forcipomyiinae, it’s a little easier. OK, that's quite a lot of them with common names. But if you need to be more exact than that, then learning the latinate, scientific names are a necessity.

Collembola, some of the better known mesofauna, have gained only three common names- the lucerne or clover flea, the snow flea and the Brassica or common springtail. Mites have a few more, like the red spider mite, the red velvet mite, follicle mite....

The naming of species is a process known as binomial nomenclature, the convention of ascribing a new something with two names, where the first describes its genus, the second, a species. This, incredibly, is applied across all of the relevant scientific disciplines across the world, so every time something new is described, there is a tacit agreement that everyone will call that latest new something Novaliquida latestii. And seriously, it’s italics or nothing.

And there's often jokes and insults buried in the names, preserved for posterity. There's a genus of snails called Turbo, and another one called Ba humbugi. And a parasitic moth called Heerz lukenatcha. Professor Scott Shaw named a parasitic wasp after Shakira- Aleiodes shakirae. He said, rather tenuously-

'Since parasitism by this species causes the host caterpillar to bend and twist its abdomen in various ways, and Shakira is also famous for her belly-dancing, the name seems particularly appropriate.'

There is a kind of archaeology to be found with naming species or genera, etc. Some early collembologists have had their names immortalised. Bourlet and Tullberg for example, have had their names given to Collembola families- the Bourletiellidae and Tullbergiidae respectively. Many more have been celebrated and remembered in Collembola genera and species.

The family Mackenziellidae is named after the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories of Canada, by which the only genus and species in the family was first found, living in dry moss.

Binomial nomenclature can be also useful when trying to identify a specimen. If your tiny animal has a bigger head than usual, it may well be called megalocephala or ‘big head’. Small might be minimus, or very small, minutus. See- it's pretty much English...

A palaeontologist named Marsh grew to hate his rival, Cope, so much that once, during years of barbed exchanges, he wordily attacked him by naming a fossil reptile Mesosaurus copeanus. He was probably hilarious at parties too.

A case in point. This is Womersleymeria bicornis. The first word references Womersley, a famous collembologist, while the ‘bicornis’ means two horns….

Carl Linné, the father of modern Taxonomy by Alexander Roslin- ©Nationalmuseum press

Classification and Cladistics

Classically, taxonomy and classification in Biology have followed the guidelines set out by Carl Linné, a Swedish botanist and zoologist. His name is usually latinised to Carolus Linnaeus. He was a one man revolution and probably only Darwin has had as much influence on how we see the natural world.

Interestingly, amongst countless other things he achieved, including originating and standardising the binomial naming of things, and having an inordinate fascination with making up highly sexual latin names for his classification system, he is also responsible for the scientific naming of Homo sapiens. As he used his own body to describe the species, his body has been the unopposed type specimen ever since, even though it still lies peacefully undisturbed in Uppsala Cathedral graveyard, Sweden.

Other biologists rapidly took to Linnaeus’ classification system and over the next century, tweaked and pulled and refined it. But it still needed Darwin and Wallace, with their understanding and theory of evolution to finally start making sense of the complicated and nested links between kinds.

So, Linnaeus’ formalised system of classification, updated with later modifications and the removal of non-living things from the categories, now goes like this.

Domain- Kingdom- Phyla- Class- Order- Family- Genus- Species.

Each different level is known as a taxon.

This system is by now, more than likely fatally flawed, as it groups every organism morphologically, as in, how it looks. And yet, as we now know, humans and mushrooms are more closely related than humans and plants, genetically. We are nearer to a starfish than a jellyfish, and so on. This is where cladistics has come along and messed with the system. And yet, some sort of a system is needed, to make sense and keep clarity in an increasingly complicated area.

Handy explanations follow, written by a Biology professor in the US. Hopefully I'll find out his name sometime for proper referencing. He explains the modern systems very well.

“Cladistics is a study in which groups (species, etc) are arranged on a phylogenetic tree according to the time at which they arose from other groups. For example, on a cladistic-type diagram, an earlier-evolving species would form a lower branch on the tree than one that evolved later.

Phylogeny refers to the development of a group, particularly through evolutionary lines.

Taxonomy is the biological science that deals with arranging and naming groups and organisms. When Linnaeus first developed the form of taxonomy we use today, he based his system on morphological similarities and differences. These days, it is based on known phylogenetic relationships and similarities in DNA, for example.

Systematics is a branch of Biology that deals with arrangement of taxonomic groups based on genetic relationships (usually). It’s a way of making sense out of potentially confusing data.”

Taxonomy is difficult. Every system humans come up with to describe the natural world will each focus a little better on the view but inevitably will fall short of seeing the full picture. That's the metaphor, anyway. Imperfect solutions are just how science works its way nearer to understanding a truth.

Years ago, there were two types of taxonomists- the lumpers and the splitters. One wanted to simplify categories, the other wanted to add more. On the surface, they all looked like normal people, but scratch under the surface and, while they were not exactly as different as chalk and cheese, they were certainly very different and distinctive types of chalk. Or cheese, depending on your preference. But that's only if you were a splitter. If you were a lumper, you were more likely to think that they were all just chalk. Or cheese.

These days, taxonomists have also had to accept and base their definitions through the use of DNA coding, adding a further complicating factor to the mix.

Now it might seem that this is all irrelevant, that maybe the need to catalogue and understand everything is a pointless exercise and everyone should just get a life. How does it benefit humanity whether a millipede might be a new species because it has an extra sensory hair on its tenth tergite?

'Can't people just look at a beetle and think, 'That's a pretty beetle' and get on with their day?'

Or- 'Acer pseudoplatanus? Are you flipping kidding me? How do you know that that tree doesn't call herself 'Ouwahweh'? You don't know, do you?'

And- 'You're just pulling Gaia apart with your 'science', destroying Her because you can't create. Typical arrogant white male upholding the patriarchal system.'

Or even- 'But God made everything. Who are you to question His creation?'

These are the sorts of things often said to me by crazy new age and religious types. I possibly need to find myself a better social circle.

I even met someone who was re-naming plants with her own made-up language, due to all names being made up, so what did it matter anyway? And she might have thrown in a bit about the male-dominated dominion over everything too. I can't remember now.

Well, for some, maybe it really is enough just to point at a beetle, say 'bug' and keep walking. But it's not a world I’m interested in living in.

The pursuit of knowledge and the desire to understand our natural world, our universe, are age-old and ongoing necessary parts of being an inquisitive human. And it really is incredibly fun and exciting to find new species, to share your passion with like-minded people, to be part of advancing the understanding of how everything might fit together into some coherent whole.

In conclusion, we're here for such a short time that I think that while we are here, it behoves us all to find out as much about this world we live in as we can. Why not? It's not like we've got somewhere better to be...