The biting midge larvae of Forcipomyia

Forcipomyia is a genus of biting midges in the sub-family Forcipomyiinae in the family Ceratopogonidae. And yes, they belong to the same family as those annoying midges, whining and biting and making life a black cloud of itchy hell for people wanting simply to be outside for a bit. And these strange and incredibly beautiful animals are their larvae. Knowing how adorable they look as larvae might make all the biting a little easier to bear.

While not always mentioned in the lists of soil animals and the mesofauna, I include the larvae of Forcipomyia here due to their obvious ubiquity around the world, their placement in that dark world of the soil and just by how unusual and beautiful they are.

As far as English common names go, the adult flies are known as no-see-ums or punkies in North America, as sand flies and little bastards in Australia and just midges, or the usual list of pointed swear words in the UK and New Zealand.

Much of the information below comes from Dr. Art Borkent, a worldwide expert on this group.

Turning.

Ceratopogonids can be found in a wide range of terrestrial or aquatic environments world-wide, depending on their species. Only Forcipomyia, a genus in the subfamily Forcipomyiiinae has really captured my attention though and what an incredible bunch they are.

Forcipomyia larva with yellow droplets, Oxfordshire UK

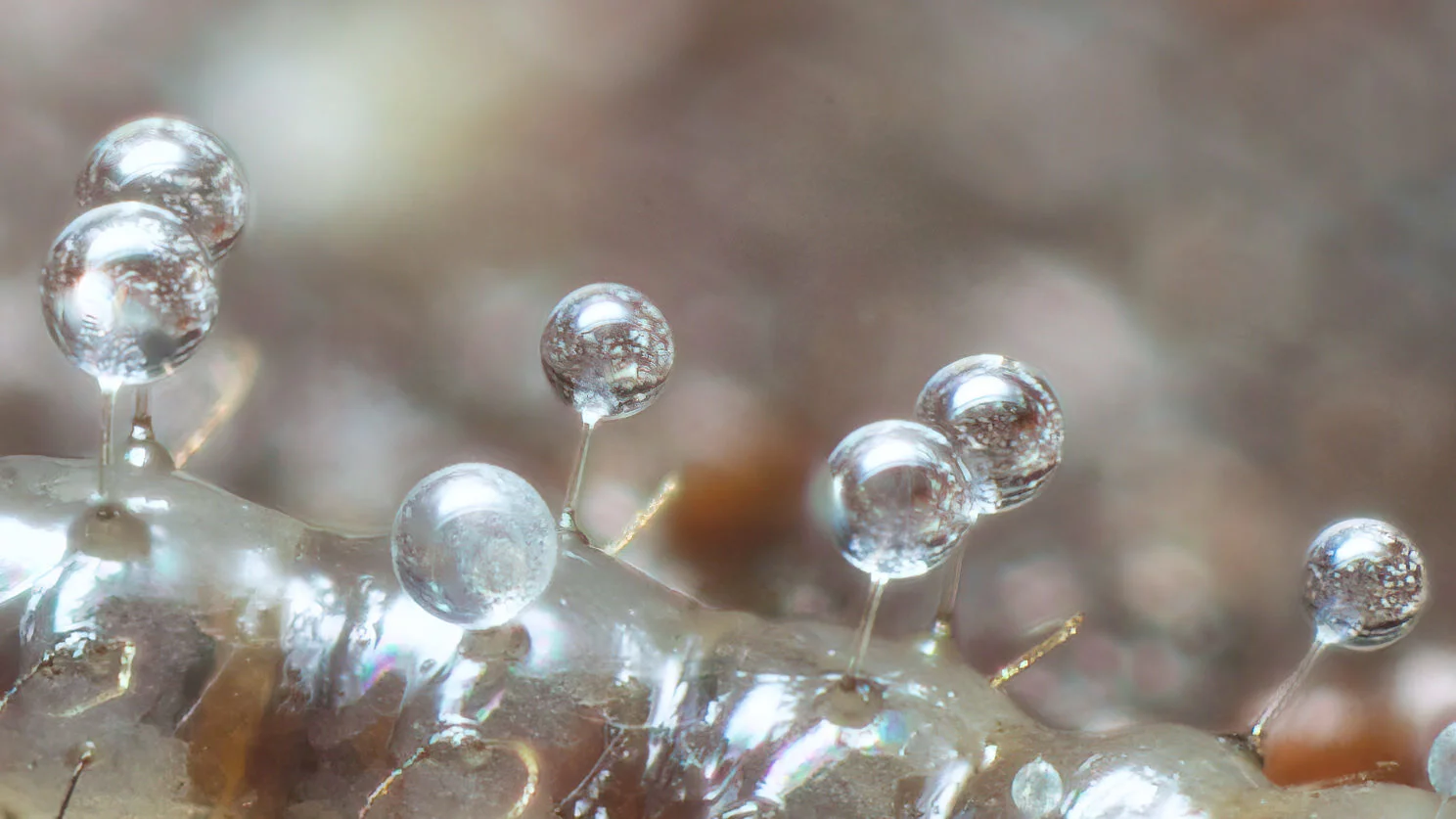

Closeup of secreted sticky droplets, Victoria, Australia Sept 2014

Larvae of many Forcipomyia are fully terrestrial, spending that period of their lives under bark and rotting logs, coasting around, eating microorganisms. Being the larvae of midges, they are tiny too, only around 3-4mm at their biggest.

The thing that really makes this genus stand out are the secretory setae on their head and body, producing a sticky, hygroscopic anti-bacterial substance that sits as droplets on top of each seta. Research suggests that the droplets are multi-functional. They appear to protect the animal against bacterial infection by seeping down onto the cuticle and keeping the cuticle moist so it can breath- the larvae have no external spiracles. There's some evidence that the droplets have repellent qualities against predators like ants.

Larvae with an owl-midge (Psychodidae) UK Feb 2015

Closeup showing the tack of the sticky droplet

Sometimes, the setae can be quite elongated, as in this specimen below, from Mexico City...

Forcipomyia larva, Mexico

...or profuse and barbed, like this guy below, from Quintana Roo, near Laguna Azul, Mexico.

Forcipomyia larva, Mexico

Here is a larva from Japan, near Kyoto with unusual clavate setae and spaecimen from Koper, Slovenia, with spine-like setae.

Forcipomyia larva, Slovenia

A cerulean blue larva from the wet tropics of North Queensland, Australia.

Forcipomyia larva, Jan 2016, Cape Tribulation rainforest

When they pupate, many species of Forcipomyia retain their larval cuticle complete with the sticky droplets on the posterior part of their abdomen, giving them continued protection as they change into an adult.

Forcipomyia pupa from East Portlemouth, Devon, UK.

Balloon animals and the Hussars

And then we come to all these guys. Unfortunately, my attempts to raise the different larvae to adults have failed so far. So their species will have to remain a mystery for now.

They appear to be unrecorded larval forms of a few Forcipomyia species, with an unknown process of making waxy balloons and tufts on the top of secretory setae. Obviously, over millions of years, secretory setae have been re-appropriated for several different uses (Borkent, pers. comm.), driven by environmental and predatory stimuli. I've only ever found the first three species in Australia, being extremely common in Tasmanian rainforests as well as on the mainland. The first time I saw one, I described it to a friend as a balloon animal, which stuck.

They seem to use the balloons as a predator distraction, waving and flicking them as they move along. They detach very easily, possibly giving the larva time to escape, very slowly. The balloons can be grown back but have to be rather energy-intensive to maintain. The stimulus or stimuli that drove these bizarre changes would be fascinating to discover.

Milkshake Hills, NW Tasmania Dec 2015

Spion Kop, NW Tasmania Dec 2015

And then there's this one below, from Binna Burra, Lamington National Park in Queensland, Australia, which has tubes rather than balloons...

This next species is different again, though they all act in the same way, just travelling around logs, spreading coolness where-ever they go.

From St. Patrick's Head, St. Helens, NE Tasmania.

A Hussar's busby

I've been calling these ones Hussars, due to their profuse plumes of waxy plumeness.

Especially similar is this yellow-topped larva below. A truly amazing form, from Cape Tribulation, in the wet tropics of Australia.

Apologies for the quality. It was filmed on my iPhone, complete with grain, over-exposure and camera shake. It's a wonder I uploaded it onto YouTube at all...

In disguise

These are yet other species of Forcipomyia, acting more like a Caddis fly larva. The first was photographed in regenerating bush, Tairua, NZ. They cover themselves in found plant detritus, using the sticky extrusions on their backs to hold it all together. Here, they’ve used mainly fern sporangia. For scale, fern spangia are smaller than dust to the naked eye, and around 0.3mm to 5mm big. This curious habit is probably to deter predators by better blending in with its environment.

The strange, extended part over the head seems to be a species wide habit, with a similar build in all the specimens I saw. Maybe it acts as a fake body part, distracting predators from the real one with movement. But how they achieve all this is a mystery.

Regenerating bush, Tairua, New Zealand, February 2016

And then I found this guy in some rotten wood, amongst the cacti and scorpions. It was found in Mexico City, 11,000 km from the other one, having to make do with bits of wood.

Balloon Festival

Saving the best until last. This species at least, has an antecedent from 1956, in the recording of a subgenus and new species, F. (Metaforcipomyia) cerifera by Saunders from under logs in a forest near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

They are impossibly stunning larvae. They move in what can only be described as a dignified and majestic manner, like a slow cruise ship, or an elderly statesman sweeping past in heavy robes. They seem completely unaware that they're just larvae of yet another biting midge.

Larva from Tairua, NZ, February 2014

Thames Feb 2016

And here, one of the four main spherical shapes is in the process of growing back. When you consider their environment, on the underside or inside of rotting logs, it's even harder to believe that the waxy tubes and balloons could be sustained as well as they are.

While nearly all photos of these are from New Zealand, they are also common in Tasmania and Northern Queensland, giving a hint of their temperature tolerance and range, The photo below is from Cape Tribulation, in Northern Queensland, Australia.

Forcipomyia larva, Cape Tribulation, Australia. 2016

Thames NZ, February 2016